Introduction: What is a Credit Crunch and Why Does It Matter?

A credit crunch is more than just a temporary tightening of lending standards—it’s a sudden and severe contraction in the availability of credit across an economy. When banks and financial institutions sharply restrict lending, raise borrowing costs, and impose stricter approval criteria, even creditworthy individuals and businesses may find themselves locked out of financing. This isn’t merely about higher interest rates; it reflects a deeper erosion of confidence among lenders, often triggered by fears over declining asset values, rising defaults, or broader economic instability.

The ripple effects of such a financial squeeze touch nearly every part of society. For households, it can delay major life decisions like buying a home or financing education. For small enterprises, it threatens survival by cutting off essential working capital. At the national level, a prolonged credit crunch can stall economic momentum, deepen recessions, and lead to lasting structural damage. Recognizing how and why credit dries up—and how to prepare for it—is vital for anyone navigating modern financial landscapes.

The Core Mechanics: What Causes a Credit Crunch?

Behind every credit crunch lies a complex web of economic imbalances and institutional missteps. These events don’t occur in isolation but are often the result of multiple pressures building beneath the surface of an apparently stable financial system. Understanding the root causes helps identify warning signs and informs both preventive and responsive strategies.

Asset Bubbles and Excessive Risk-Taking

One of the most common triggers of a credit crunch is the collapse of an asset bubble fueled by speculative excess and lenient lending practices. During periods of economic optimism, banks and investors often lower their guard, extending loans to riskier borrowers or accepting inflated property values as collateral. Real estate booms, such as the U.S. housing surge in the mid-2000s, are classic examples where easy credit led to unsustainable price increases. As more subprime borrowers entered the market with adjustable-rate mortgages, the foundation of the financial system quietly weakened.

When interest rates eventually rose or economic conditions shifted, defaults surged, home prices plummeted, and the value of mortgage-backed securities collapsed. Financial institutions that had heavily invested in these instruments faced massive losses, undermining their ability to lend. The resulting shock caused a rapid pullback in credit supply—a textbook case of how speculative mania can morph into systemic crisis.

Financial Market Instability and Loss of Confidence

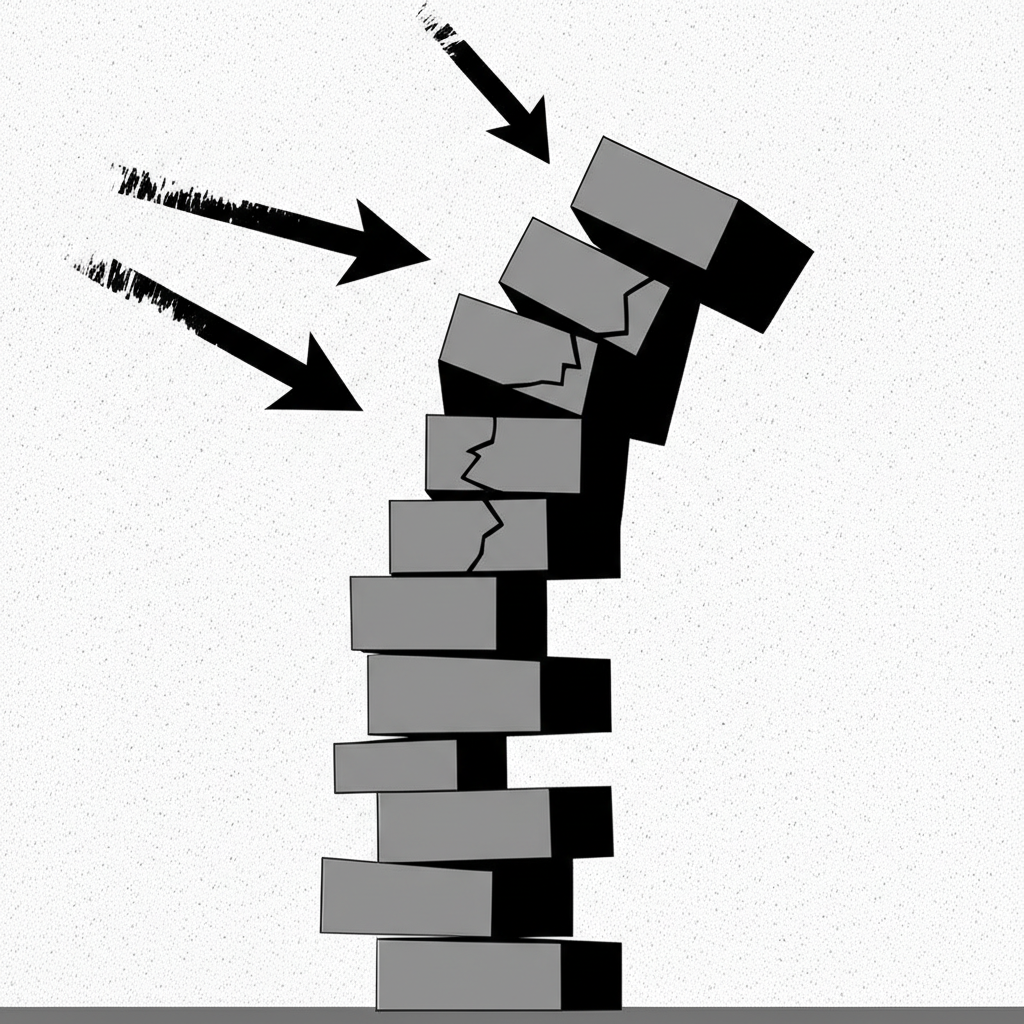

Perhaps even more dangerous than falling asset prices is the sudden loss of trust between financial institutions. The health of the banking system depends on liquidity flowing smoothly, especially through the interbank market, where banks lend to each other overnight to meet reserve requirements. But when doubts emerge about a bank’s solvency—especially if it holds large quantities of questionable assets—lenders hesitate. This caution can quickly spiral into a full freeze.

In such scenarios, banks begin hoarding cash, refusing to lend even to seemingly stable peers. Without access to short-term funding, otherwise healthy institutions can face liquidity shortages, pushing them toward insolvency. This domino effect amplifies the credit squeeze far beyond any single failing institution, turning isolated problems into a systemic emergency.

Regulatory Failures and Systemic Shocks

Weak or poorly enforced regulations often lay the groundwork for future crises. In the years leading up to the 2008 financial meltdown, many financial institutions operated with dangerously high leverage, complex derivatives were poorly understood, and capital buffers were insufficient. Regulators failed to keep pace with financial innovation, allowing risks to accumulate quietly within the system.

Then, when an external shock hits—be it a global recession, geopolitical conflict, or commodity price collapse—these hidden vulnerabilities are exposed. The shock triggers widespread loan defaults, forces asset write-downs, and prompts a flight to safety. In response, both regulators and financial institutions clamp down on lending to preserve capital, inadvertently deepening the credit crunch. This pattern underscores the importance of proactive oversight and stress testing to prevent systemic fragility.

Far-Reaching Economic Impacts of a Credit Crunch

The consequences of a credit crunch extend well beyond Wall Street or corporate boardrooms—they reshape entire economies and affect everyday lives. Once lending contracts, the flow of money slows down, disrupting investment, consumption, and employment.

Stagnation of Economic Growth (GDP Decline)

Credit is the lifeblood of economic activity. When businesses can’t borrow to fund new projects or maintain operations, investment declines. Consumers, facing higher loan costs and stricter approval processes, delay big purchases like homes and vehicles. This dual slowdown in spending and investment erodes aggregate demand, leading to a measurable drop in Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Historically, severe credit crunches have been closely linked to recessions, with output contracting and recovery taking years. The lag in restoring credit availability often prolongs the downturn, making economic rebounds sluggish.

Rising Unemployment Rates

As revenue falls and financing becomes scarce, companies look to cut costs. Workforce reductions are often the fastest way to do so. Hiring freezes become common, and layoffs spread across sectors—from construction and retail to manufacturing and services. Small businesses, which typically lack deep reserves and rely heavily on credit, are especially vulnerable. The result is a sharp rise in unemployment, which not only increases personal hardship but also reduces consumer spending further, reinforcing the downward spiral.

Deflationary or Disinflationary Pressures

While inflation dominates headlines during boom times, a credit crunch can tilt the economy toward the opposite danger: deflation. With demand weakened, businesses struggle to maintain prices. Consumers delay purchases in anticipation of lower prices, further depressing sales. In extreme cases, falling wages and prices create a deflationary trap where debt burdens effectively increase in real terms, discouraging borrowing and investment. Even disinflation—the slowing of price growth—can complicate monetary policy, limiting central banks’ ability to stimulate the economy through traditional rate cuts.

Impact on Government Finances

Governments feel the strain as well. Lower economic activity translates into reduced tax receipts from income, sales, and corporate profits. At the same time, public spending rises due to increased demand for unemployment benefits, food assistance, and other social programs. To counter the downturn, governments may launch stimulus initiatives, further widening budget deficits. The combination of higher debt and slower growth can constrain fiscal flexibility for years, affecting long-term priorities like infrastructure, education, and healthcare.

How a Credit Crunch Affects Businesses and Investment

Businesses across industries face mounting pressure when credit markets seize up. Even profitable firms with solid fundamentals can find themselves in survival mode when short-term financing vanishes.

Restricted Access to Capital and Funding

The first sign of a credit crunch for many companies is the sudden difficulty in securing loans. Banks tighten underwriting standards, demand more collateral, and impose steeper interest rates. Lines of credit may be frozen or reduced without notice. Startups and fast-growing firms, which often depend on external financing for expansion, are hit hardest. Without access to working capital, routine operations like payroll, inventory procurement, and supplier payments become precarious.

Reduced Investment and Business Expansion

With capital both scarce and expensive, long-term planning takes a backseat. Projects that once seemed promising—new factories, product development, technology upgrades—are shelved. Companies focus on cost control rather than innovation. This retrenchment not only stalls immediate growth but also weakens future competitiveness. Over time, the economy loses momentum as productivity gains slow and entrepreneurial energy wanes.

Increased Bankruptcy Rates, Especially for SMEs

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are particularly exposed during a credit crunch. Unlike large corporations, they rarely have access to bond markets, private equity, or diversified revenue streams. Their survival often hinges on bank relationships and timely access to credit. When those channels close, many SMEs face immediate liquidity crises. Unable to cover basic expenses or refinance maturing debt, they default. A 2010 study by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) found that SMEs in Asian economies experienced sharp credit contractions during financial stress, underscoring their fragility in the face of systemic shocks.

Supply Chain Disruptions

One of the less visible but equally damaging effects of a credit crunch is the disruption it causes in supply chains. Many businesses operate on trade credit, buying goods now and paying suppliers later. When financing dries up, suppliers may demand cash upfront or shorten payment terms, straining the cash flow of their customers. If downstream firms can’t meet these demands, the chain breaks—factories halt production, deliveries are delayed, and inventory shortages ripple outward. This interconnectedness means a financial crisis can quickly turn into an operational one, affecting industries far removed from banking.

Effects on Consumers, Households, and Personal Finance

For ordinary people, a credit crunch alters the financial landscape in tangible and often painful ways. Access to credit becomes harder, job security wavers, and household budgets tighten.

Tighter Lending Standards for Mortgages and Loans

Homebuyers and borrowers quickly feel the pinch. Mortgage approvals become harder to obtain, with lenders requiring higher credit scores, larger down payments, and more documentation. Auto loans, personal loans, and student financing follow suit. Even those with good credit may face higher interest rates or reduced loan amounts. The dream of homeownership slips further out of reach for many, while major purchases become unaffordable without credit support.

Decreased Consumer Spending and Confidence

Fear of job loss, combined with tighter credit and economic uncertainty, leads households to spend less and save more. Discretionary spending on travel, dining, and electronics drops. This pullback is significant because consumer spending accounts for a large share of GDP in most developed economies. As demand weakens, businesses see lower revenues, leading to more layoffs and further reducing consumer confidence—a self-reinforcing cycle that deepens the downturn.

Challenges in Managing Debt and Credit Cards

For those already carrying debt, a credit crunch can be financially devastating. Refinancing options vanish, and variable-rate loans or credit card balances may see sudden rate hikes. Monthly payments rise, squeezing household budgets. Some consumers face credit limit reductions or account closures, even if they’ve made timely payments. These actions, while intended to reduce lender risk, can push individuals toward default, damaging credit histories and compounding financial distress.

The 2008 Global Financial Crisis: A Landmark Credit Crunch Example

The 2008–2009 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) remains the most severe credit crunch in recent memory, offering a stark illustration of how quickly financial stability can unravel.

Precursors and Initial Triggers

Years of relaxed lending standards, especially in the U.S. housing market, set the stage for disaster. Banks issued subprime mortgages to borrowers with weak credit, often with low introductory rates that reset sharply upward after a few years. These risky loans were bundled into complex securities—mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and collateralized debt obligations (CDOs)—and sold globally. Investors, drawn by high yields, underestimated the risks. As housing prices soared, the bubble appeared sustainable—until it wasn’t.

Unfolding of the Credit Crunch and Its Immediate Effects

When adjustable rates reset and unemployment rose, wave after wave of borrowers defaulted. Foreclosures spiked, property values collapsed, and the securities built on these loans lost much of their value. Financial institutions holding them faced massive losses. Trust evaporated. The interbank lending market froze, with banks refusing to lend to one another. Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy in September 2008, sending shockwaves through global markets. AIG, a major insurer of mortgage-backed securities, required a government bailout. Panic spread, and credit markets seized up almost overnight.

Global Repercussions and Policy Responses

The crisis quickly went global. European banks with exposure to U.S. securities faced similar losses. Stock markets plunged, economies contracted, and unemployment soared. In response, central banks took unprecedented action. The Federal Reserve slashed interest rates to near zero, injected trillions in liquidity, and launched Quantitative Easing (QE) to stabilize markets. Governments rolled out stimulus packages and rescued failing banks. Later, reforms like the Dodd-Frank Act aimed to strengthen oversight, increase capital requirements, and reduce systemic risk. The GFC showed both the fragility of interconnected financial systems and the power of coordinated policy intervention.

Navigating a Credit Crunch: Strategies for Resilience

While no one can fully insulate themselves from a systemic crisis, preparation and adaptability can significantly reduce vulnerability.

For Businesses: Building Financial Prudence and Diversifying Funding

Strong financial management during good times builds resilience in bad ones. Companies should maintain healthy cash reserves, minimize reliance on short-term debt, and manage receivables and inventory efficiently. Relying solely on traditional bank financing is risky—diversifying into alternative sources like private equity, venture capital, crowdfunding, or government-backed loan programs can provide critical lifelines. Cultivating relationships with multiple lenders also improves negotiating power. Above all, avoiding excessive leverage ensures long-term solvency even when credit markets freeze.

For Individuals: Strengthening Personal Finance and Emergency Planning

Personal financial discipline is key. Establishing an emergency fund covering three to six months of essential expenses creates a buffer against income loss. Paying down high-interest debt reduces monthly obligations and improves financial flexibility. Maintaining a strong credit score increases the chances of securing credit when it’s needed most. Additionally, developing new skills or pursuing side income streams can reduce dependence on a single job, offering greater stability during economic turbulence.

The Role of Fintech in Crisis Resilience and Mitigation

Financial technology has the potential to reshape how credit is accessed and managed during crises. Platforms like peer-to-peer lending, online lenders, and digital banking services can offer alternatives to traditional banks, especially for underserved SMEs. Real-time data analytics and automated underwriting may allow for faster, more accurate risk assessment. Blockchain and smart contracts could enhance transparency in lending and settlement processes.

However, fintech also introduces new risks. Decentralized finance (DeFi) platforms, while innovative, often lack regulatory safeguards and can be highly volatile. Algorithm-driven lending may amplify pro-cyclical behavior, tightening credit even more during downturns. Without proper oversight, these systems could contribute to instability rather than reduce it. The key lies in integrating fintech responsibly—harnessing its speed and efficiency while ensuring accountability and consumer protection.

Conclusion: Preparing for Future Financial Headwinds

A credit crunch is not just a financial event—it’s a societal stress test. Its impact stretches from corporate boardrooms to family kitchens, from global markets to Main Street businesses. By restricting the flow of credit, it undermines investment, suppresses consumption, and erodes confidence. The 2008 crisis revealed how quickly trust and liquidity can vanish, turning a manageable correction into a full-blown economic emergency.

Yet history also offers lessons in resilience. Businesses that maintain strong balance sheets and diverse funding options are better equipped to weather the storm. Individuals who prioritize savings, manage debt wisely, and plan ahead can navigate uncertainty with greater confidence. Policymakers play a crucial role through timely intervention, prudent regulation, and international coordination.

As financial systems evolve, with fintech reshaping access to capital and globalization increasing interdependence, vigilance remains essential. The goal isn’t to eliminate risk—such a feat is impossible—but to build systems and habits that absorb shocks, adapt to change, and recover with strength. By learning from the past and preparing for the future, economies and individuals alike can face financial headwinds not with fear, but with foresight.

What are the immediate economic consequences felt during the onset of a credit crunch?

During the onset of a credit crunch, immediate consequences include:

- Increased Borrowing Costs: Interest rates for loans rise significantly.

- Reduced Loan Availability: Banks become highly selective, making it difficult to secure new loans or refinance existing ones.

- Declining Asset Values: Prices of assets like real estate and stocks may fall as liquidity dries up and forced sales occur.

- Business Liquidity Issues: Companies, especially SMEs, struggle to access working capital, potentially leading to operational disruptions.

- Decreased Consumer Spending: Households postpone major purchases due to uncertainty and tighter credit.

How do restrictive lending policies during a credit crunch specifically impact small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)?

SMEs are disproportionately affected by restrictive lending policies because:

- They often rely heavily on traditional bank loans for working capital, expansion, and day-to-day operations.

- They typically have fewer alternative funding sources compared to larger corporations.

- Tighter collateral requirements and higher interest rates can quickly make borrowing unfeasible.

- This can lead to cash flow problems, delayed investment, reduced hiring, and ultimately, increased bankruptcy rates.

What role did the housing market play in causing the 2008 credit crunch, and are similar risks present today?

The housing market was central to the 2008 credit crunch. A bubble fueled by subprime mortgages and securitization led to widespread defaults when interest rates rose. This caused the value of mortgage-backed securities to collapse, triggering a crisis of confidence in the financial system.

Today, while direct parallels to the subprime crisis are less apparent due to stricter regulations, risks can emerge from other areas. For instance, high levels of corporate debt, rapid growth in certain asset classes (e.g., tech stocks), or emerging market vulnerabilities could present new forms of systemic risk if left unchecked. Regulators continuously monitor for new asset bubbles and excessive risk-taking.

Beyond financial institutions, which other sectors of the economy are most vulnerable to the ripple effects of a credit crunch?

Beyond financial institutions, highly vulnerable sectors include:

- Real Estate and Construction: Directly impacted by reduced mortgage availability and investment.

- Automotive: Relies heavily on consumer financing and business loans for production.

- Retail (especially discretionary goods): Suffers from decreased consumer spending and confidence.

- Manufacturing: Affected by reduced demand, supply chain disruptions, and difficulty financing inventory or capital expenditures.

- Small Businesses: As discussed, they face severe challenges in accessing capital.

What proactive measures can individuals take to safeguard their personal finances in anticipation of or during a credit crunch?

Individuals can safeguard their finances by:

- Building an Emergency Fund: Saving 3-6 months’ worth of living expenses.

- Reducing Debt: Prioritizing paying down high-interest debt, especially credit cards.

- Maintaining a Good Credit Score: Paying bills on time and keeping credit utilization low.

- Diversifying Income Streams: Exploring side hustles or developing new skills to reduce reliance on a single source of income.

- Reviewing Budgets: Identifying and cutting unnecessary expenses.

How do central banks typically intervene to mitigate the severity and duration of a credit crunch?

Central banks typically intervene using:

- Interest Rate Cuts: Reducing benchmark rates to encourage lending and borrowing.

- Liquidity Injections: Providing emergency funding to banks to ensure they have enough cash.

- Quantitative Easing (QE): Purchasing government bonds and other assets to inject liquidity and lower long-term interest rates.

- Forward Guidance: Communicating future policy intentions to stabilize expectations.

- Lender of Last Resort: Acting as a backstop to prevent bank failures and maintain financial system stability.

Is a credit crunch always followed by a recession, or can the economy recover without one?

While credit crunches frequently precede or accompany recessions due to their severe impact on economic activity, it is not an absolute certainty that every credit crunch will result in a full-blown recession. The severity and duration of the credit crunch, as well as the effectiveness of policy responses by central banks and governments, play crucial roles. A mild or short-lived credit tightening, coupled with robust economic fundamentals and swift policy action, might allow an economy to avoid a formal recession, experiencing only slower growth or disinflation instead.

What are the key differences between a credit crunch, a liquidity crisis, and a solvency crisis?

These terms are related but distinct:

- Credit Crunch: A sudden and severe reduction in the availability of credit, making it hard to borrow regardless of creditworthiness.

- Liquidity Crisis: A situation where an entity (or system) has assets but cannot readily convert them into cash to meet short-term obligations. A credit crunch can cause a liquidity crisis by freezing interbank lending.

- Solvency Crisis: Occurs when an entity’s liabilities exceed its assets, meaning it cannot meet its long-term obligations. A severe credit crunch can push otherwise solvent businesses into insolvency if they cannot access short-term funds.

How might global geopolitical events or trade disputes contribute to the likelihood or severity of a credit crunch?

Global geopolitical events or trade disputes can heighten the risk of a credit crunch by:

- Increasing Uncertainty: Creating economic instability that makes lenders more risk-averse.

- Disrupting Supply Chains: Leading to higher costs and cash flow problems for businesses, increasing their borrowing needs while reducing their ability to repay.

- Triggering Capital Flight: Investors withdrawing funds from perceived risky regions, reducing liquidity.

- Impacting Investor Confidence: Reducing appetite for risk, leading to tighter credit conditions globally.

- Imposing Sanctions: Directly limiting access to global financial markets for targeted entities or countries.

What are the long-term societal and economic lessons learned from past credit crunch events?

Long-term lessons from past credit crunches include:

- Importance of Financial Regulation: Stronger oversight is crucial to prevent excessive risk-taking and asset bubbles.

- Need for Systemic Resilience: Financial systems must have sufficient capital buffers and robust stress testing.

- Central Bank Responsiveness: The critical role of central banks as lenders of last resort and in implementing unconventional monetary policies.

- Fiscal Prudence: Governments need healthy fiscal positions to respond effectively during crises.

- Consumer and Business Preparedness: The value of emergency savings, diversified funding, and prudent debt management.

- Interconnectedness of Global Finance: Crises can spread rapidly across borders, necessitating international cooperation.

留言