Navigating the Data Labyrinth: Why the NHS Needs Transformation

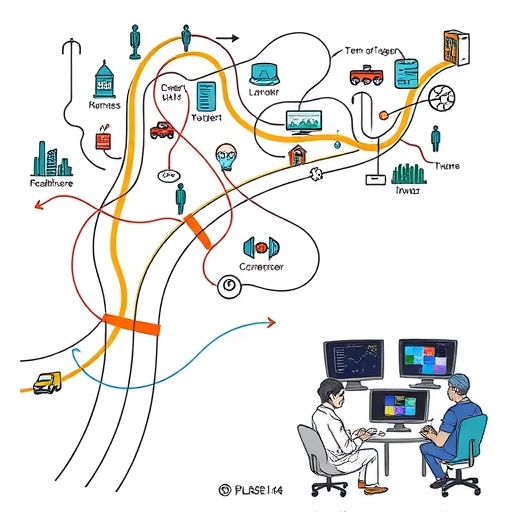

Imagine your personal health journey as a sprawling, complex map. Every doctor’s visit, every prescription, every hospital stay marks a point on that map. Now, imagine that each of these points is drawn on a separate, unlinked piece of paper, stored in a different office, perhaps even a different city. This fragmented reality is, in many ways, the challenge that has long plagued the National Health Service (NHS) in England. For decades, the NHS has grappled with a significant, underlying issue often described as a “structural flaw” in its data management.

What exactly does this mean for us, the patients, and for the healthcare professionals dedicated to our well-being? It means that crucial information about your medical history, your ongoing treatments, or even your allergies might be trapped in disparate legacy systems, making seamless information exchange a formidable task. This lack of interoperability across NHS trusts can lead to frustrating delays in patient record transfers, hinder effective care coordination, and impede the swift, efficient allocation of resources. Think about the precious time lost when a new specialist has to piece together your medical narrative from scratch, or when a hospital struggles to discharge patients efficiently due to a bottleneck in administrative data flows. This isn’t merely an inconvenience; it can have profound impacts on patient outcomes and the overall operational efficiency of one of the world’s largest healthcare systems.

- This fragmented system can lead to patient data being inaccessible when it matters most, potentially compromising safety and effectiveness of care.

- Healthcare professionals often have limited visibility into a patient’s complete medical picture, resulting in missed diagnoses or unnecessary duplication of tests.

- Delays in data access can extend waiting times, exacerbate patient anxiety, and ultimately affect health outcomes.

The imperative for a radical digital transformation within the NHS is undeniable. The COVID-19 pandemic, in particular, brutally exposed the vulnerabilities of these disconnected systems, highlighting the urgent need for a unified, coherent data infrastructure. How can we optimize vaccination programs, manage critical supply chains for essential medical equipment, or recover from the immense backlog in elective care if the foundational data isn’t accessible, integrated, and actionable? The answer is clear: we can’t, not effectively. This foundational need is precisely what the NHS aims to address with its ambitious new initiative: the Federated Data Platform (FDP).

The FDP represents a strategic leap towards a future where patient data flows intelligently, securely, and seamlessly, empowering healthcare professionals with the insights they need to deliver superior care. It promises to enable better population health management, allowing us to identify health trends, predict needs, and intervene proactively. It seeks to streamline patient discharge processes, freeing up beds and reducing waiting lists. It aims to optimize resource allocation, ensuring that the right resources are in the right place at the right time. But as with any monumental undertaking involving sensitive public data, particularly within a beloved institution like the NHS, this journey towards modernization is not without its complexities, challenges, and indeed, its controversies.

Unpacking the Federated Data Platform (FDP): A Vision for Integrated Care

So, what exactly is the Federated Data Platform (FDP), and how is it envisioned to revolutionize the sprawling landscape of NHS data? At its core, the FDP is designed as a secure, integrated system that will bring together fragmented data from across the NHS. Think of it not as a single, centralized database where all patient information is dumped into one giant bucket, but rather as a sophisticated network, allowing different NHS trusts and Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) to share and analyze their data more effectively, while maintaining control over their own datasets. This “federated” approach is key: it aims to connect existing data points rather than consolidate them wholesale, preserving local ownership and governance where appropriate.

The FDP’s primary objective is to enhance the NHS’s ability to coordinate care, manage resources, and improve patient outcomes. Consider a scenario where a patient moves between different hospitals or receives care from multiple specialists. Currently, their records might not easily follow them, leading to repeated information gathering, potential delays, and even risks if critical details are missed. The FDP seeks to overcome this by enabling a more fluid and secure exchange of patient information, painting a more complete picture for clinicians at the point of care. This means healthcare professionals could have a more holistic view of a patient’s journey, leading to more informed decisions and personalized treatment plans.

Beyond individual patient care, the FDP has broader, systemic ambitions. It aims to significantly improve operational efficiency across the NHS. For instance, by providing clearer insights into bed availability, staff rostering, and equipment supply chains, the platform could help managers optimize resource allocation, reduce waste, and improve response times. During peak demand or health crises, the ability to quickly analyze population health trends and identify areas of greatest need becomes invaluable. We saw the critical need for such capabilities during the Covid-19 pandemic, where rapid data analysis was essential for vaccine rollout, hospital capacity management, and understanding disease spread. The FDP is expected to build upon these lessons, providing a robust infrastructure for future public health challenges.

| System Objectives | Goals |

|---|---|

| Streamline Discharge Processes | Reduce waiting lists and free hospital beds. |

| Optimize Resource Allocation | Ensure timely delivery of medical resources. |

| Improve Population Health Management | Identify health trends and proactively intervene. |

Moreover, the platform is intended to support crucial NHS priorities, such as tackling the backlog in elective care. By offering a clearer view of waiting lists across different trusts and specialties, it could help identify opportunities for patients to be treated sooner, perhaps at a different facility with available capacity. It could also streamline patient discharge processes, identifying bottlenecks and facilitating smoother transitions from hospital to community care. In essence, the FDP promises to transform raw data into actionable intelligence, empowering the NHS to deliver more responsive, efficient, and patient-centered care. This vision of a more interconnected, data-driven NHS is compelling, yet its implementation hinges not just on technological prowess, but also on navigating complex questions of trust and ethical responsibility, particularly concerning its chosen technological partner.

The Architect of Integration: Palantir’s £480 Million Mandate

Against this backdrop of urgent necessity for data transformation, NHS England made a landmark decision, awarding a highly significant contract to an American data analytics firm: Palantir Technologies. The contract, primarily for the development and deployment of the Federated Data Platform (FDP), has been widely reported with varying figures, most prominently cited as £330 million over seven years, with a potential to reach up to £480 million. This substantial investment underscores the critical importance NHS England places on this digital overhaul, signaling its commitment to leveraging advanced technology for its future.

So, why Palantir? For many, the name itself evokes a sense of both cutting-edge capability and profound controversy. The company, co-founded by tech mogul Peter Thiel, has built a reputation for its powerful, often opaque, data analysis software, primarily catering to intelligence agencies, governments, and large corporations. Its flagship product, Foundry, is designed to integrate vast, disparate datasets and allow users to model, analyze, and make decisions based on complex information. This core capability is precisely what NHS England believes is required to knit together its fragmented data landscape, addressing the “structural flaw” we discussed earlier.

Under the terms of the contract, Palantir’s role is not merely as a software vendor; it is positioned as the primary technology provider, tasked with deploying its Foundry platform to serve as the technological backbone for the FDP. This involves integrating various data sources, developing analytical tools, and providing the infrastructure to support key NHS functionalities. The scope is vast, encompassing everything from population health initiatives and supply chain management to vaccination program oversight and the critical task of elective care recovery. Essentially, Palantir is being entrusted with building the central nervous system for data within the NHS, a system upon which the future efficiency and effectiveness of the health service will heavily rely.

| Partner Company | Contribution |

|---|---|

| Accenture | Strategic advice and system integration. |

| PwC | Project management and data governance frameworks. |

| NECS | Domain-specific knowledge and support services. |

| Carnall Farrar | Strategic advice on healthcare operations. |

However, Palantir isn’t working alone. The contract also involves a consortium of other key partners, including well-known names like Accenture, PwC, NECS, and Carnall Farrar. This multi-partner approach suggests a complex implementation strategy, drawing on diverse expertise in technology, consulting, and healthcare operations. While Palantir provides the core platform, these partners are expected to contribute to implementation, customization, and ensuring the FDP integrates seamlessly with existing NHS workflows. This collaborative effort is crucial for a project of this magnitude, but the sheer scale of the investment and the controversial nature of the lead partner have inevitably drawn intense scrutiny, inviting us to look closer at the shadows that accompany this significant deal.

Beyond the Figures: Understanding Palantir’s Foundry Software and Key Partners

When we talk about Palantir’s £480 million mandate, it’s not just about a large sum of money; it’s about the sophisticated technology and the intricate web of partnerships that underpin the Federated Data Platform (FDP). At the heart of Palantir’s offering to the NHS is its proprietary software, Foundry. What makes Foundry so compelling, and why is it considered suitable for the monumental task of unifying NHS data?

Foundry is an enterprise data integration and analytics platform designed to solve highly complex data challenges. Imagine you have countless pieces of information, perhaps patient records from different hospitals, operational data from various departments, supply chain logistics, and public health statistics. These pieces are often in different formats, stored in different systems, and speak different “languages.” Foundry acts as a universal translator and organizer. It connects to these disparate data sources, cleanses and transforms the data, and then integrates them into a coherent, navigable “digital twin” of the real-world system. This allows users – in the NHS’s case, healthcare planners, analysts, and potentially clinicians – to explore relationships, identify patterns, and run simulations that would be impossible with fragmented data.

For the NHS, Foundry’s capabilities translate into practical applications:

- Population Health Management: Identifying trends in disease outbreaks, understanding health inequalities, and targeting public health interventions more effectively.

- Supply Chain Optimization: Tracking the flow of medicines, equipment, and other vital resources, ensuring they reach where they are needed most, preventing shortages or waste.

- Elective Care Recovery: Analyzing waiting lists, resource availability, and patient pathways to identify efficiencies and reduce treatment backlogs.

- Operational Efficiency: Streamlining everything from patient flow within hospitals to staff deployment across trusts.

This kind of deep analytical capability is where Palantir argues its value lies, promising to turn raw data into actionable insights for improved patient care and system efficiency.

However, the FDP is not solely a Palantir endeavor. The success of such a vast digital transformation project relies heavily on collaboration. The contract specifically mentions a consortium of partners working alongside Palantir:

- Accenture: A global professional services company known for its vast experience in consulting, technology services, and outsourcing. Their role likely involves strategic advice, system integration, and change management.

- PwC (PricewaterhouseCoopers): Another “Big Four” professional services network, offering expertise in consulting, audit, and tax services. Their contribution could be in areas like project management, data governance frameworks, and financial oversight.

- NECS (North of England Commissioning Support): An NHS organization providing business and commissioning support services. Their inclusion brings valuable domain-specific knowledge and ensures the FDP aligns with existing NHS operational realities.

- Carnall Farrar: A specialist healthcare consultancy. They likely provide strategic advice on healthcare operations and policy, ensuring the FDP delivers tangible benefits to patient care and system performance.

This multi-faceted partnership aims to combine Palantir’s advanced technological platform with deep industry knowledge and implementation expertise. Yet, the strength of any chain is in its weakest link, and despite the formidable capabilities of these partners, the focus of concerns, as we will explore next, remains disproportionately on Palantir itself and its long, controversial history.

A History Under Scrutiny: Palantir’s Controversial Roots and Data Privacy Fears

When a company like Palantir, with its origins steeped in the world of intelligence and surveillance, enters the sensitive realm of public healthcare, it’s inevitable that questions of trust, ethics, and data privacy will emerge. Palantir Technologies was co-founded by Peter Thiel, a prominent venture capitalist with strong ties to the US intelligence community, and significantly, it received early funding from the CIA’s venture capital fund, In-Q-Tel. This foundational link to spy technology and government surveillance has indelibly shaped its public image and the perception of its intentions.

Over the years, Palantir has amassed a history of highly controversial engagements, far removed from the humanitarian mission of a national health service. Its technology has been deployed by various government agencies for purposes that have raised serious ethical alarms. Consider its involvement in:

- Predictive Policing: Systems that analyze vast amounts of data to predict where crimes might occur, often criticized for exacerbating existing biases in law enforcement and disproportionately targeting certain communities.

- Immigration Enforcement: Contracts with Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in the US, supporting activities related to deportations and border surveillance.

- Military Operations: Providing data analysis for drone strikes and counter-insurgency efforts in conflicts like those in Iraq and Afghanistan.

These past activities, whether for national security or law enforcement, paint a picture of a company deeply embedded in sensitive, often coercive, data-driven operations. When such an entity is entrusted with the highly personal and confidential health data of millions of citizens, it’s perfectly natural for significant privacy fears to arise. Are we to believe that the same tools used for surveillance and deportation will be confined purely to patient care in the NHS?

Medical bodies and privacy campaigners have voiced grave concerns. The British Medical Association (BMA), the Doctors’ Association UK, patients’ groups, and privacy advocates have consistently highlighted the potential risks. Despite NHS England’s assurances that no third party can access health data without explicit permission, and that data will not be used for research or include GP records in the national platform, skepticism persists. The fundamental question is: can a company whose core business model revolves around maximizing the utility of data, often for highly sensitive purposes, truly be trusted with the sanctity of patient confidentiality in a public health context?

The worry is not just about direct data access, but about the very nature of Palantir’s technology and its potential for “mission creep.” Once a powerful data analysis platform is in place, how can we guarantee that its capabilities won’t be extended beyond their stated purpose, perhaps to link health data with other government datasets in ways unforeseen or unintended by the public? This inherent tension between technological power and the safeguarding of individual privacy forms a significant shadow over the NHS-Palantir contract, a shadow compounded by questions surrounding the transparency and fairness of the procurement process itself.

The Procurement Puzzle: Questions of Fairness and Transparency

A contract of such immense value and strategic importance to the NHS, especially one awarded to a company with Palantir’s background, naturally invites intense scrutiny into the procurement process itself. Was the bidding fair? Was it transparent? Or were there factors at play that gave an unfair advantage to the eventual winner? Critics argue that the process was far from exemplary, raising numerous red flags that fuel public distrust and allegations of favoritism.

One of the most prominent criticisms revolves around the **unduly short bidding period**. Reports suggest that potential bidders were given as little as one month to prepare their comprehensive proposals for a contract worth hundreds of millions of pounds and affecting the entire national health system. For a project of this scale and complexity, a one-month window is considered exceptionally tight by industry standards. This brevity raises serious questions: Did it allow enough time for a truly competitive field to emerge? Or did it inadvertently favor an incumbent or a company already intimately familiar with the NHS’s internal workings and data infrastructure?

| Criticism Areas | Concerns Raised |

|---|---|

| Short Bidding Period | Limited time for fair competition. |

| Allegations of Favoritism | Potential biases towards known entities. |

| Incumbent Advantage | Leveraging prior work for competitive edge. |

Indeed, there are historical claims that Palantir has been “buying its way in” to public sector contracts, particularly within the UK government. This accusation is often linked to allegations of “backdoor meetings” and political donations. While the specifics are often difficult to substantiate publicly, the perception that Palantir has unusual levels of access or influence within government circles creates an uneven playing field for other potential bidders. Such allegations, even if unproven, chip away at the fundamental principle of fair competition in public procurement, which is meant to ensure taxpayers get the best value and that decisions are made on merit, not connections.

The context of Palantir’s prior involvement with the NHS during the Covid-19 pandemic also plays a role here. Palantir provided its Foundry software to the NHS on a pro-bono basis, later transitioning to a paid contract. While this initial “emergency” work was justified by the pandemic’s urgency, some critics view it as a strategic move that allowed Palantir to embed its technology and familiarize key stakeholders with its platform, thus giving it a significant “incumbent advantage” when the larger FDP contract came up for tender. If a company has already proven its capabilities within an organization, and its technology is already integrated to some extent, it inherently possesses a competitive edge over rivals starting from scratch.

For a public institution like the NHS, maintaining absolute transparency and perceived fairness in its procurement processes is paramount for safeguarding public trust. When allegations of rushed bidding, political influence, and incumbent advantage surface, they not only undermine confidence in the specific contract but also cast a long shadow over the broader integrity of public sector decision-making. These concerns are further amplified by the unfolding ethical and geopolitical controversies surrounding Palantir’s CEO, which we must now address directly.

Geopolitical Currents: Palantir’s Stance on Global Conflicts and its Ethical Ripple

Perhaps the most potent and escalating controversy surrounding the NHS-Palantir contract stems from recent geopolitical events and the outspoken stance of Palantir’s CEO, Alex Karp. This dimension introduces a severe ethical conflict for an institution like the NHS, which is founded on principles of universal care and neutrality, and has triggered widespread outrage and fervent calls for the contract’s cancellation. The issue is deeply sensitive and complex, touching upon humanitarian concerns and international law.

Alex Karp has been an unequivocal and vocal supporter of Israel, particularly regarding its military operations in Gaza. Not only has he expressed strong political alignment, but Palantir itself has direct contracts with the Israeli military, providing its advanced data analytics technology for what it describes as “war-related missions.” This is not merely a CEO’s personal opinion; it represents the company’s active involvement in a conflict that has caused immense human suffering and drawn severe criticism from international bodies and human rights organizations.

The core of the ethical dilemma for the NHS and the UK public lies in the alleged “war on hospitals” in Gaza. Multiple reports from UN agencies, medical organizations, and human rights groups detail devastating attacks on healthcare infrastructure in Gaza, including hospitals, clinics, and ambulances. Healthcare workers have been detained, tortured, and killed. The health system in Gaza has been systematically dismantled, leading to widespread famine, dehydration, and a spiraling infectious disease crisis. Against this backdrop, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) has issued an interim judgment stating that Israel’s actions could plausibly constitute genocide.

For many health workers, patients, and human rights advocates in the UK, contracting with a company actively aiding a military engaged in actions described as plausible genocide and a “war on hospitals” creates an untenable ethical position for the NHS. How can a health service dedicated to healing and care knowingly partner with a firm directly supporting a conflict accused of destroying healthcare? This perceived complicity has sparked fervent protests, including pickets outside NHS England offices, and impassioned calls from medical bodies and public figures for the contract to be terminated immediately.

The ethical ripple effect of this geopolitical entanglement is profound. It challenges the very moral fabric of the NHS and risks undermining its fundamental commitment to humanitarian principles. For patients, particularly those from marginalized communities or with global ties, the knowledge that their sensitive health data might be managed by a company involved in such conflicts can erode trust and create profound discomfort. This intersection of national healthcare, advanced technology, and international ethics presents NHS England with an unprecedented crisis of public confidence, compelling us to consider the broader implications for public trust and data governance in the UK.

The Humanitarian Dilemma: The NHS, Gaza, and the Crisis of Public Trust

The ethical entanglement stemming from Palantir CEO Alex Karp’s vocal support for, and the company’s direct involvement with, Israeli military operations in Gaza has propelled the NHS-Palantir contract into a profound humanitarian dilemma. This isn’t just about data privacy or procurement fairness; it’s about the very soul of the NHS and its foundational values, creating a deepening crisis of public trust that could jeopardize the entire Federated Data Platform initiative.

For millions across the UK and globally, the events unfolding in Gaza are a humanitarian catastrophe of unparalleled scale. The destruction of hospitals, the targeting of healthcare workers, and the severe deprivation of basic necessities have elicited widespread condemnation. When the International Court of Justice issues an interim judgment indicating that actions could plausibly constitute genocide, the gravity of the situation cannot be overstated. In this context, for the NHS – an institution born out of a post-war commitment to universal care, free at the point of need – to be seen as directly or indirectly linked to such actions through its primary technology partner is, for many, an unbearable contradiction.

Health workers, who embody the humanitarian spirit of the NHS, have been particularly vocal. Organizations like Health Workers for a Free Palestine have led protests, stating emphatically that “Our NHS is not for sale, and it should not be complicit in crimes against humanity.” They argue that a company providing technology to a military engaged in what they term a “war on hospitals” is fundamentally incompatible with the ethical standards and public mission of the NHS. This sentiment resonates deeply with patients’ groups and privacy advocates who see the contract not just as a technological arrangement, but as a moral compromise.

| Crisis Factors | Impacts on Trust |

|---|---|

| Ethical Incongruity | Conflict with humanitarian mission. |

| Reputational Risk | Endorsing actions that are widely condemned. |

| Erosion of Confidence | Loss of public faith in data handling. |

| Professional Dissent | Opposition from the medical community. |

The crisis of public trust emerges from several interconnected facets:

- Ethical Incongruity: The perceived conflict between the NHS’s humanitarian mission and Palantir’s alleged role in enabling human rights abuses.

- Reputational Risk: The potential for the NHS to be seen as endorsing or enabling actions that are widely condemned internationally.

- Erosion of Confidence: If the public loses faith in the ethical compass of the NHS’s leadership, it becomes harder for them to trust how their sensitive medical data will be handled, regardless of technical safeguards.

- Professional Dissent: The strong opposition from within the medical community itself suggests a profound internal struggle and disillusionment among the very people who will be using the FDP.

This public dissent is not a minor hurdle; it represents a significant challenge to the successful implementation and acceptance of the FDP. A data platform, no matter how technologically advanced, cannot succeed without the buy-in and trust of both the public whose data it processes and the healthcare professionals who must use it. The humanitarian dilemma presented by Palantir’s geopolitical stance is forcing the NHS to confront a critical question: At what cost does innovation come, and can public trust, once eroded, ever be fully restored?

Safeguarding Our Data: The Imperative for Robust Governance and Oversight

The controversies surrounding the NHS-Palantir contract, particularly those related to data privacy and Palantir’s checkered past, underscore a fundamental truth: the success of any large-scale data transformation in healthcare hinges not just on the technology itself, but on exceptionally robust data governance and independent oversight. For us, as individuals whose most sensitive health information will be part of the Federated Data Platform (FDP), the question is paramount: how will our data truly be safeguarded?

NHS England has made repeated assurances: “no third party can access health data without explicit permission,” and “data will not be used for research or include GP records in the national platform.” These are crucial commitments. However, history teaches us that intentions, while important, must be backed by concrete, enforceable mechanisms. What does “explicit permission” truly mean in practice? Will patients have clear, easy-to-understand opt-out options? How will the boundaries for “research” be defined and enforced, especially given the analytical capabilities of a platform like Foundry?

Effective data governance extends beyond mere technical security; it encompasses the legal, ethical, and operational frameworks that dictate how data is collected, stored, used, and shared. For a system like the FDP, this means:

- Clear Data Access Protocols: Who within the NHS, and potentially within Palantir, will have access to what types of data, under what circumstances, and for what defined purposes? This needs to be transparent and auditable.

- Independent Auditing: Regular, external audits by independent bodies are crucial to verify compliance with privacy regulations (like GDPR) and ethical guidelines, ensuring that data usage remains strictly within the agreed-upon parameters.

- Patient Consent and Control: Empowering patients with genuine control over their data, including clear information about how it will be used and easily accessible mechanisms to manage their consent preferences.

- Strong Accountability Mechanisms: What are the consequences for any misuse or breach of data? Are there clear lines of accountability within the NHS and with its partners?

- Ethical Review Boards: Beyond legal compliance, establishing robust ethical review processes for any new applications or analyses performed using the FDP data.

The concerns raised by organizations like the BMA and Doctors’ Association UK are not merely theoretical; they stem from a deep understanding of the vulnerabilities inherent in large data systems and the potential for scope creep if oversight is lax. They highlight the tension between the push for data utility and the fundamental right to privacy. Can the NHS genuinely ring-fence sensitive patient information when its partner has a business model historically focused on maximizing data connections for diverse applications?

Ultimately, safeguarding our data requires more than assurances; it demands proactive, transparent, and enforceable governance structures. It necessitates an ongoing dialogue between the NHS, its technology partners, healthcare professionals, and the public. Without such a robust framework and unwavering commitment to oversight, the ambition of the Federated Data Platform risks being overshadowed by persistent anxieties over privacy and the erosion of the trust that is the lifeblood of our health service.

Charting the Future: Balancing Innovation, Ethics, and Public Confidence

The NHS-Palantir contract stands as a potent symbol of the complex interplay between urgent healthcare modernization, the transformative power of advanced technology, and profound ethical considerations. As we’ve explored, the Federated Data Platform (FDP) holds immense promise for revolutionizing data management within the NHS, offering the potential to streamline operations, enhance patient care coordination, and tackle critical challenges like elective care backlogs. The vision of a more efficient, data-driven health service is compelling, a beacon of innovation in a sector desperately in need of progress.

However, this journey towards digital transformation is inextricably linked to the controversies that shadow Palantir. The company’s origins in intelligence, its history of controversial surveillance activities, and particularly its CEO Alex Karp’s recent vocal support for, and active involvement with, Israeli military operations in Gaza, have ignited a storm of opposition. These concerns are not peripheral; they strike at the heart of public trust, ethical responsibility, and the humanitarian principles that underpin the NHS. For an institution that relies so heavily on the confidence of its citizens, navigating these moral complexities is as crucial as implementing the technology itself.

How, then, does the NHS chart a path forward? It faces a formidable task: balancing the imperative for technological innovation with an unwavering commitment to ethics and the restoration of public confidence. This requires more than mere technical assurances; it demands:

- Unprecedented Transparency: Opening up the FDP’s operational frameworks, data flow pathways, and governance structures to public scrutiny and independent oversight. This includes clear, understandable communication about how sensitive patient data will be protected, used, and if ever, shared.

- Proactive Ethical Engagement: Actively addressing the ethical concerns raised by medical bodies and the public, particularly regarding Palantir’s geopolitical involvements. This might involve re-evaluating contractual terms to include stronger ethical clauses or exploring mechanisms to mitigate reputational risk.

- Empowering Public Voice: Creating genuinely accessible and impactful channels for patients and healthcare professionals to voice concerns, provide feedback, and participate in the ongoing governance of the FDP.

- Strengthening Independent Oversight: Reinforcing the role of independent bodies in auditing data access, usage, and security, ensuring accountability and adherence to privacy regulations.

The potential benefits of the FDP for patient care and NHS efficiency are significant, offering a glimpse into a future where data truly empowers healthcare. Yet, the price of that innovation cannot be the erosion of public trust or a compromise on the fundamental ethical commitments of the health service. For the NHS to truly leverage this technology and safeguard its invaluable public trust, it must navigate these challenges with unparalleled integrity, demonstrating a renewed commitment to ethical data governance and the core values that make it one of the most cherished institutions in the UK.

look nhs palantir 480mFAQ

Q:What is the Federated Data Platform (FDP) and its purpose?

A:The FDP is a secure, integrated system intended to bring together fragmented healthcare data across the NHS to enhance care coordination, resource management, and patient outcomes.

Q:Why was Palantir chosen as a partner for the FDP?

A:Palantir was selected for its advanced data integration capabilities, which are essential for addressing the NHS’s data management challenges.

Q:What concerns have been raised about the NHS’s partnership with Palantir?

A:Concerns include issues related to data privacy, Palantir’s controversial history in surveillance, and the potential ethical implications of its geopolitical involvements.

留言