The Long Game: Why Long Term Value Investing Isn’t Dead, Just Different

For decades, Value Investing has been the bedrock of successful long-term wealth creation. Championed by legendary figures like Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger, the core principle is simple: buying assets for less than their intrinsic worth. It sounds intuitive, right? Yet, if you’ve followed the markets over the past fifteen years, particularly in the United States, you might wonder if this time-tested approach still works. Value stocks have faced significant headwinds, lagging far behind their Growth Investing counterparts. But is Value truly obsolete, or is its struggle merely a localized phenomenon and a reflection of specific, perhaps transient, market conditions? As we delve into the nuances, we’ll explore the global divergence in Value’s performance and assess whether the stage is set for a potential comeback.

Key Points to Note:

- Value investing focuses on purchasing undervalued assets, while growth investing emphasizes future earnings potential.

- The performance of value stocks has been affected by macroeconomic factors, such as interest rates and market concentration.

- Global markets have shown diverse performance trends, with some international regions demonstrating strong value stock resilience.

Historical Foundations: What is Value Investing?

At its heart, Value Investing is rooted in the concept of buying stocks that appear to be trading for less than their fundamental or ‘book’ value. This idea gained academic traction through the work of researchers like Eugene Fama and Kenneth French, who found that, over long periods, stocks with low price-to-book ratios (companies trading cheaply relative to their balance sheet assets) tended to outperform the market and growth stocks.

Think of it like buying a piece of real estate significantly below the cost it would take to rebuild it, or acquiring a business for less than the liquidation value of its assets. The expectation is that eventually, the market will recognize the true value, and the stock price will rise to reflect it. Historically, looking at data from the U.S. stock market index since 1926, value stocks have indeed delivered higher annualised returns compared to growth stocks, often cited with a premium of around 2.5% per year. This long-term efficacy is a powerful argument for the strategy’s enduring relevance.

But are all cheap stocks ‘value’? This is where the definition has evolved. Just because a stock has a low Price-to-Book or P/E Ratio doesn’t automatically make it a good investment. Sometimes, a stock is cheap for a very good reason – the business is failing, the industry is in terminal decline, or it faces insurmountable challenges. This led to a refinement of the value approach.

This modern interpretation suggests that true Value Investing involves more than just quantitative screening. It requires deep Fundamental Analysis to understand the business, its industry dynamics, management quality, and future prospects. It’s about buying a piece of a great business at a reasonable price, rather than a piece of a mediocre business at a very low price. This distinction becomes critical when trying to understand recent market performance.

The Buffett Evolution: Beyond Balance Sheets

While early definitions of value focused heavily on tangible assets and balance sheet metrics, Warren Buffett‘s approach, often described as ‘quality value,’ added a crucial layer. Buffett isn’t just looking for cheap assets; he’s looking for high-quality businesses trading at a fair price, or ideally, below their intrinsic value. The key difference? His focus on the durability and profitability of the business itself, not just its current balance sheet.

Buffett and Munger emphasized the concept of an ‘economic moat’ – a sustainable competitive advantage that protects a company’s long-term profitability and market share. This moat could come from brand recognition, network effects, high switching costs for customers, or proprietary technology. A company with a strong moat can consistently generate high returns on capital over many years, even if its initial Price-to-Book ratio isn’t the lowest in the market.

This modern interpretation suggests that true Value Investing involves more than just quantitative screening. It requires deep Fundamental Analysis to understand the business, its industry dynamics, management quality, and future prospects. It’s about buying a piece of a great business at a reasonable price, rather than a piece of a mediocre business at a very low price. This distinction becomes critical when trying to understand recent market performance.

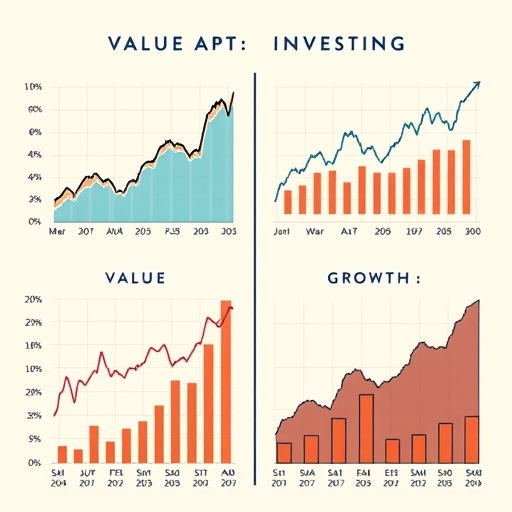

A Decade of Disappointment: Value’s Struggle in the US Market

Despite its impressive long-term track record, Value Investing, especially in the US Market, has endured a challenging period since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2007-2008. Between 2007 and 2020, Growth Investing significantly and persistently outperformed Value. While there were brief periods where Value showed strength (like parts of 2016 and 2021-2022), the dominant trend was clear: growth stocks, particularly in the technology sector, were the market leaders.

| Year | Value Performance | Growth Performance |

|---|---|---|

| 2016 | Strength | Stable |

| 2017 | Weak | Strong |

| 2021 | Bounce Back | High |

| 2022 | Decline | Persisted |

This underperformance wasn’t just a minor blip; it was severe and prolonged. According to analysis referencing data like the UBS Global Investment Returns Yearbook and Morningstar indices, the gap between US Growth and Value returns widened considerably. This left many traditional value fund managers scratching their heads and questioning the future of their strategy. For investors who entered the market in this era, the historical data praising value might have seemed irrelevant or even misleading.

Then, after a relative rebound for value in 2021-2022 amidst rising interest rates, the gap began to widen again in late 2022 and into 2023-2024, largely driven by the extraordinary performance of a handful of mega-cap technology stocks often referred to as the Magnificent Seven (Mag7). So, what factors conspired to create this difficult environment for US Value?

Unpacking the Headwinds: Why US Value Lagged

Several interconnected factors contributed to the prolonged period of Value Investing underperformance in the United States after the GFC. Understanding these helps us determine if they are permanent structural shifts or cyclical forces that might eventually reverse.

- The ultra-low Interest Rates prevalent for over a decade negatively impacted value stock performance.

- The rise of Index Investing has shifted capital away from active value strategies.

- The extreme Market Concentration among a few technology stocks has hampered value stock growth.

One major culprit was the era of ultra-low Interest Rates that persisted for over a decade. Central banks, like the Federal Reserve, slashed rates to near zero to stimulate the economy after the GFC. Low-interest rates have a significant impact on how we value assets. In discounted cash flow (DCF) models, which analysts use to estimate the intrinsic value of a company, future earnings are discounted back to their present value. When discount rates (influenced by interest rates) are low, those future earnings are worth more in today’s dollars.

This disproportionately benefits growth stocks because a larger portion of their expected profits lies far in the future. Investors were willing to pay a premium today for the promise of large profits years down the line. Conversely, value stocks, which often generate more of their earnings and cash flow in the near term (sometimes even paying high dividends), received less of a relative boost from low rates. Their more immediate cash flows were already being valued relatively highly.

Another powerful force was the explosive growth of Index Investing, also known as Passive Investing. Over the past decade, trillions of dollars have flowed out of actively managed funds and into low-cost index funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs) that simply track a market index like the S&P 500. What does this have to do with value? Passive funds buy stocks based on their weight in an index, usually determined by market capitalization. As large-cap growth stocks grew rapidly, their weight in these indices increased, triggering more passive inflows, which in turn drove their prices even higher in a self-reinforcing cycle.

This tidal wave of passive capital has been argued to reduce the effectiveness of traditional active strategies, including value. With such large flows directed automatically by market cap, there’s less capital specifically seeking out undervalued companies based on fundamental analysis. Some argue this diminishes the market’s natural Price Discovery mechanism for smaller or out-of-favor companies, which are often found in the value category or among Small-Cap Stocks.

Finally, the extreme Market Concentration observed in the U.S. Market, particularly with the rise of the Magnificent Seven (Mag7) – Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Nvidia, Meta, and Tesla – played a huge role. These few companies came to represent an enormous portion of the market’s total capitalization and generated a disproportionate share of the returns. Historically, periods of extreme market concentration, such as the “Nifty Fifty” boom in the early 1970s or the late 1990s Technology bubble, have often coincided with periods where value stocks underperform. Money floods into a narrow group of perceived winners, leaving the broader market, including many value names, behind.

For instance, between 2010 and early 2024, U.S. equities returned an annualized 10% after inflation, vastly outperforming the rest of the world combined (Developed and Emerging Markets averaged 2.6%). This highlights how much of the global equity returns were concentrated in the U.S., and within the U.S., how much was concentrated at the very top, heavily favouring large-cap growth.

A Different Narrative: Value’s Resilience Overseas

While Value Investing struggled in the U.S. Market, a strikingly different story unfolded in many International Markets (Global ex-US). In regions like Developed Asia and Emerging Markets, value stocks have not only held their own but have often outperformed their growth counterparts in recent years.

Why this divergence? Several factors seem to be at play. Firstly, the sector composition of international markets often differs significantly from the highly tech-concentrated U.S. Market. International indices tend to have heavier weightings in sectors like Financials, Energy, Industrials, and Materials – sectors that often contain traditional value stocks. For example, banks like HSBC, Banco Santander, and BNP Paribas, energy giants like Shell and TotalEnergies, and major mining or industrial companies feature prominently in international indices.

| Region | Performance of Value Stocks | Performance of Growth Stocks |

|---|---|---|

| Developed Asia | Outperformed | Stable |

| Emerging Markets | Strong Returns | Moderate |

| Global ex-US | Positive Trend | Varied |

The rebound in commodity prices and energy stocks following events like the Russia-Ukraine conflict provided a significant boost to value indices heavily weighted in the Energy Sector. Similarly, the prospect of rising Interest Rates globally, even before the Fed’s hiking cycle, started to benefit the Financials Sector, another traditional home for value stocks. These sector tailwinds were less pronounced in the tech-heavy U.S. market.

Secondly, market concentration has generally been less extreme outside the U.S. While there are large, dominant companies globally (e.g., TSM in Taiwan, Nestle in Europe), the phenomenon of a small handful of stocks driving such a vast proportion of overall market returns has been more acute in the US. This means international markets might offer a broader field for traditional value investors to find opportunities overlooked by large passive flows.

Furthermore, some argue that international markets have been less susceptible to the ‘growth at any price’ mentality that dominated the US market for periods. Valuation matters more when the underlying economic growth is perhaps less spectacular than the narrative surrounding leading US tech giants. This created an environment where fundamental valuation disparities became more apparent, offering fertile ground for value hunters.

Consider data comparing the Morningstar Global ex-US Value Total Market Exposure Index and its growth counterpart. Over certain recent periods, the value index has clearly demonstrated superior performance, standing in stark contrast to the U.S. experience. This suggests that the principles of Value Investing are not broken; their application and effectiveness vary depending on the specific market environment and geographical location.

The Global Hunter: Finding Value Opportunities Today

Given the divergent performance, where are Value Investing opportunities most likely to be found today? While pockets of value always exist, even in expensive markets, the international landscape appears particularly promising according to many value managers. Strategies employed by firms like Ninety One (formerly Investec Asset Management) highlight how skilled value investors are navigating this environment.

They often categorize opportunities based on different types of value. There’s ‘Deep Value‘, which focuses on companies trading at extremely low valuations relative to their assets or earnings, often facing significant challenges but with potential for operational turnaround or asset realization. This can be like finding a neglected gem in the rough.

Then there are ‘Fallen Angels‘ – companies that were once highly regarded growth stocks or quality businesses that have fallen out of favor due to temporary setbacks, industry downturns, or idiosyncratic issues. Their stock prices have plummeted, but the underlying business quality, or moat, may still be intact or recoverable. Buying these requires careful analysis to distinguish between temporary problems and permanent impairment.

Cyclical Leaders are another focus. These are companies in cyclical industries (like basic materials, industrials, or energy) that are well-managed and positioned to thrive when their sector enters a favorable part of the economic cycle. They might look cheap at the bottom of the cycle but have significant earnings power when demand picks up.

Finally, ‘Special Situations’ involve companies facing specific events that could unlock value, such as spin-offs, mergers, restructurings, or management changes. These often involve complex analysis but can yield substantial returns if the event creates a catalyst for market value recognition.

Implementing these strategies requires patience, rigorous Fundamental Analysis, and a willingness to be contrarian – buying when others are fearful or simply overlooking a situation. Let’s look at some specific examples from a market like the UK to see these strategies in action.

Case Studies in Action: UK Examples

The UK Market has been cited by some value investors as a particularly fertile ground for opportunities, partly due to lower valuations relative to the US and specific market dynamics (like pension fund outflows historically depressing domestic stock valuations). Let’s examine a few examples cited by managers like Alessandro Dicorrado from Ninety One.

Melrose Industries (Melrose) is an interesting case. Melrose operates a “buy, improve, sell” model for industrial businesses. They acquired GKN, an aerospace and automotive engineering group, restructured it, and spun off the automotive division. The remaining aerospace business is focused on a healthier, growing end market (aircraft components and services). Despite its complex structure, the stock was perceived by some value investors as trading below the potential value of its constituent parts and future aerospace earnings power, representing a potential ‘Special Situation’ and ‘Cyclical Leader’ opportunity in the aerospace upcycle.

Jet2 (Jet2 plc), an airline and package holiday company, presented a ‘Fallen Angel’ opportunity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Travel was severely disrupted, and the stock price collapsed. However, value investors assessing the situation recognized that unlike many competitors burdened by debt, Jet2 had a strong balance sheet, excellent customer service reputation, and loyal base. They believed the pandemic was a temporary setback and the company was well-positioned to recover sharply when travel resumed. This required conviction to buy into a distressed sector based on long-term business quality.

NatWest (NatWest Group), one of the large UK banks, represents a more traditional ‘Deep Value’ opportunity, particularly given its low Price-to-Book ratio and high dividend yield. While the banking sector faces ongoing challenges and regulatory scrutiny, investors buying NatWest for value saw a stable, albeit slow-growing, franchise trading at a significant discount to tangible book value. The high Dividend Payout Ratio provided an immediate return while waiting for potential market recognition of its underlying value, or simply enjoying the substantial income stream, even if the business wasn’t deemed ‘amazing’ in terms of growth prospects.

These examples illustrate that finding value requires looking beyond the headlines and conducting thorough Fundamental Analysis. It involves assessing the balance sheet strength, cash flow generation, management strategy, and competitive position, often finding these positive attributes in companies that the broader market is overlooking or discounting excessively due to short-term issues or lack of exciting growth narratives.

Is the Tide Turning? Potential Catalysts for a Value Rebound

While the past decade was challenging for US Value, many proponents argue that conditions are now ripening for a potential shift in market leadership back towards value stocks, potentially globally. What are the potential catalysts that could drive this turnaround?

- The return to higher, more ‘normal’ Interest Rates is a significant factor.

- The scale of the current valuation disparity between growth and value is at historical extremes.

- Questions surrounding the sustainability of the recent extraordinary returns from large growth stocks may reshape perception.

Firstly, the return to higher, more ‘normal’ Interest Rates is a significant factor. As central banks like the Federal Reserve have hiked rates from near zero to curb inflation, the discount rate used in valuation models has risen. This makes future earnings less valuable in present terms, disproportionately impacting the valuations of long-duration growth stocks whose value is heavily dependent on profits expected many years from now. Conversely, companies with strong current earnings and cash flow, often found in the value category, become relatively more attractive. Higher rates also tend to benefit traditional value sectors like Financials.

Secondly, the sheer scale of the valuation disparity between growth and value has reached historical extremes. According to data cited by firms like Morningstar and others, a broad basket of U.S. value stocks is currently trading near its lowest valuation level relative to growth stocks in over two decades. This wide gap suggests that value stocks are statistically ‘cheap’ compared to growth stocks, creating potential for a mean reversion or ‘catch-up’ effect. While cheap can always get cheaper, such wide historical spreads have often preceded periods of value outperformance.

Thirdly, there are questions surrounding the sustainability of the recent extraordinary returns from the largest growth stocks. While narratives around AI are powerful, the vast capital expenditures required for the ‘AI arms race’ by companies like the Magnificent Seven raise questions about the ultimate return on investment. If these investments don’t translate into commensurate profit growth, the market might reassess their elevated valuations. Meanwhile, value stocks, often in less glamorous sectors, might be quietly generating solid, albeit lower-growth, profits and returning capital to shareholders through dividends or buybacks.

Finally, shifting geopolitical dynamics and potential changes in global capital flows could play a role. The era of seemingly unchallenged “American exceptionalism” and seamless globalization that benefited US tech giants could face headwinds from rising protectionism, trade tensions (like potential new tariffs), and geopolitical instability. If global capital flows become less focused on a narrow set of US tech winners and diversify more towards other regions and sectors, it could benefit international markets and the value stocks prevalent within them. Discussions around supply chain diversification, energy security, and regional manufacturing could favour more traditional industrial or materials companies, many of which fall into the value category.

None of these catalysts guarantee a swift or smooth rotation, and market timing is always challenging. However, they represent powerful forces that could, over time, shift the scales back in favour of the value style.

The Enduring Principles: Patience and Price Discovery

So, is Long Term Value Investing still a viable strategy? Based on the evidence, yes, absolutely. While its performance has been challenged in specific markets under unique conditions, the fundamental logic of buying something for less than it’s worth remains sound. The recent struggles in the US don’t negate the long-term historical outperformance or the current opportunities present in other markets and specific sectors globally.

In a world increasingly dominated by Index Investing, the role of active investors, particularly value investors conducting rigorous Fundamental Analysis, becomes even more crucial. Who is doing the essential work of Price Discovery if everyone is just buying the index based on market cap? Active value managers seeking out undervalued companies help ensure markets remain somewhat efficient by correcting mispricings.

Successful Value Investing demands patience. It often requires holding investments for years while waiting for the market to recognize the intrinsic value. It’s a strategy that is often contrarian, requiring you to buy when others are pessimistic and sell when they are overly optimistic. It’s about thinking like an owner of the business, not just a trader of a stock certificate.

For both investment beginners looking for a solid framework and experienced traders seeking to diversify their approach beyond growth or momentum, understanding and applying value principles can be incredibly rewarding over the long term. It provides a disciplined way to approach markets, focusing on the underlying business fundamentals rather than just price charts or fleeting trends.

The path forward for value might be bumpy, and the timing of a significant rotation is uncertain. However, the historical track record, the current wide valuation spreads, and the potential macro-economic shifts suggest that overlooking Value Investing, especially on a global scale, would be a mistake for any serious long-term investor.

Conclusion: Value Persists in a Changing World

We’ve explored the historical triumphs and recent tribulations of Long Term Value Investing. We’ve seen how a combination of ultra-low Interest Rates, the surge in Index Investing, and extreme Market Concentration, particularly in the U.S. Market and its concentration in stocks like the Magnificent Seven, created a challenging environment for value stocks for over a decade. Yet, we’ve also highlighted the resilience and outperformance of value in many International Markets, benefiting from different sector compositions and less extreme concentration.

The potential catalysts – a return to higher rates, the historically wide valuation gap between value and growth, questions about the profitability of future growth investments, and evolving geopolitical landscapes – suggest that the narrative could be changing. While past performance is never a guarantee of future results, the fundamental logic of buying assets below their intrinsic value remains as compelling as ever.

For you, the investor, this means understanding the context. Value isn’t broken; its performance is subject to market cycles and specific conditions. The principles of conducting thorough Fundamental Analysis, identifying businesses with durable competitive advantages (moats), maintaining a margin of safety by buying below intrinsic value, and exercising patience are still paramount.

Whether you focus on Deep Value, Fallen Angels, or quality businesses trading at reasonable prices, the pursuit of value requires discipline and a long-term perspective. In a market that is increasingly passive, active value investors play a vital role in Price Discovery. The journey of a value investor is often one of swimming against the tide, but for those willing to put in the work and exercise patience, the potential rewards over the long term remain significant. Embrace the principles, stay disciplined, and look globally for opportunities – Value Investing continues to be a powerful tool in the investor’s arsenal.

long term value investingFAQ

Q:What is value investing?

A:Value investing is a strategy where investors buy stocks that appear to be undervalued relative to their intrinsic worth.

Q:Why have value stocks underperformed recently?

A:Factors like low interest rates, market concentration in growth stocks, and the rise of index investing have contributed to the underperformance of value stocks.

Q:Are value investing principles still relevant today?

A:Yes, the fundamental logic of value investing remains sound, and opportunities can still be found in various sectors and markets.

留言